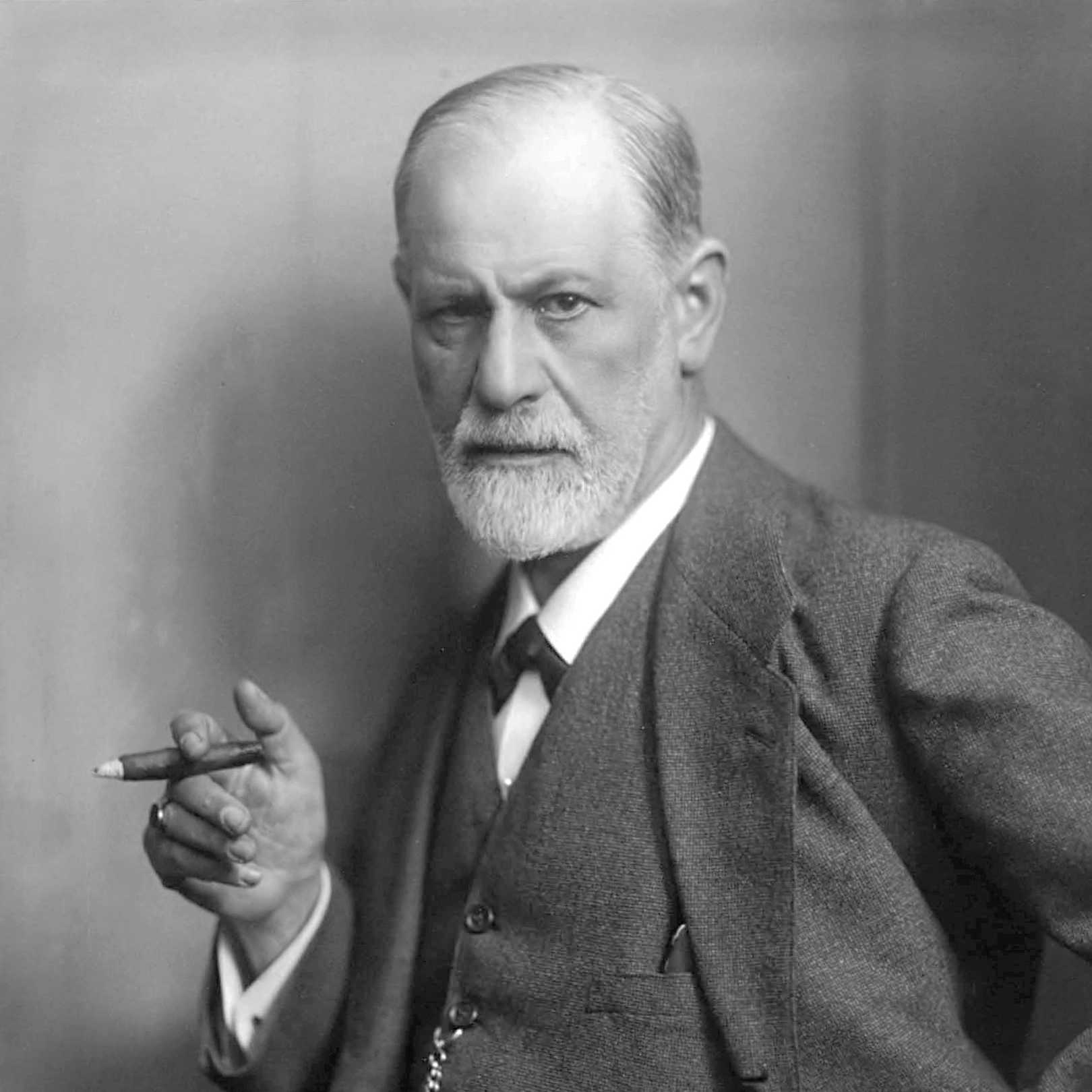

As you know, Sigmund Freud started out as a medical doctor in Vienna. His specialty was the brain and nervous disorders.

As part of his postgraduate education, Freud studied in Paris with Jean-Martin Charcot, the leading neurologist of his day. Back in Vienna, he collaborated with Josef Breuer and eventually wrote a book with him.

Both Charcot and Breuer had been experimenting with medical hypnosis. Freud’s only use for hypnosis was as a way to get patients to talk more freely. After listening to his patients talk, Freud formulated theories on the way his patients’ minds worked. He called his process “psycho-analysis.”

Part of Freud’s theory covered human psychosexual development. Here he observed that later developments build on earlier ones. But, he says — and you can read this in his 1915 introductory lectures at the University of Vienna, published in English in 1920 [1] — there is a “danger of this development by stages.” It’s possible under some circumstances for later development to be undone. The individual falls back to a previous level. Here’s how Freud puts it:

Even those components which have achieved a degree of progress may readily turn backward to these earlier stages. Having attained to this later and more highly developed form, the impulse is forced to a regression when it encounters great external difficulties in the exercise of its function, and accordingly cannot reach the goal which will satisfy its strivings.

Here he is using the word “regression” to mean an involuntary return to an earlier stage of development, brought about by frustration.

In the 1920s Freud turned his attention from the psyche of the individual to the culture as a whole. During this period he published The Future of an Illusion (1927).

Keep in mind that Freud defined himself as a “godless Jew.” [2] The Future of an Illusion is a “godless Jew’s” take on religion. To my mind, it’s not a very good book. Freud must have liked it, because he sent a copy to his friend, the French writer Romain Rolland.

Rolland wrote back with his view of religion, which was quite different from Freud’s. Rolland described a sense of timelessness and limitlessness which he called the “oceanic feeling,” and which, he said, was always present in the background of his experience. Romain Rolland believed this oceanic feeling was the real source of religion.

Freud responded to Rolland’s idea in chapter 1 of his next book, Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, first published in German in 1929 and in English in 1930 under the title Civilization and Its Discontents.

After describing the oceanic feeling, Freud concluded that “the adult’s ego-feeling cannot have been the same from the beginning. It must have gone through a process of development, which cannot, of course, be demonstrated but which admits of being constructed with a fair degree of probability.” [3]

What he’s saying is that the sense of self, the sense of I-ness, which most people take for granted, hasn’t been there all along. The “oceanic feeling” was how we all experienced reality before our egos developed — before we had any sense of separateness.

Then Freud — or more accurately, a second friend of Freud’s — raised the possibility of deliberate regression, brought about by spiritual practice. This is in contrast to the involuntary regression that Freud identified as brought about by frustration. Here’s how Freud described the process of intentional regression: [4]

Another friend of mine, whose insatiable craving for knowledge has led him to make the most unusual experiments and has ended by giving him encyclopedic knowledge, has assured me that through the practices of Yoga, by withdrawing from the world, by fixing the attention on bodily functions and by peculiar methods of breathing, one can in fact evoke new sensations and coenesthesias [a coenesthesia is just a bodily awareness] in oneself, which he [meaning the second friend] regards as regressions to primordial states of mind which have long ago been overlaid. He sees in them a physiological basis, as it were, of much of the wisdom of mysticism.

So there you have it. Even in the 1920s, a few people were already aware that mysticism was essentially regressive.

What does a regressive state of consciousness feel like?

We can start with Romain Rolland’s description: “le fait simple et direct de la sensation de l’éternel (qui peut très bien n’être pas éternel, mais simplement sans bornes perceptibles, et comme océanique),” “the simple and direct fact of the feeling of the eternal (which may very well not be eternal, but simply without perceivable boundary markers, as if oceanic).” So it’s a feeling of timeless eternity and boundless space.

Then we can add from Piaget the notion that the regressive state must exist before object permanence. Jean Piaget was the Swiss psychologist who investigated children’s cognitive development. One early milestone he noticed was “object permanence.” This is the developmental stage where an object still exists in the mind of the infant, even if the object is not immediately available to the senses.

Object permanence develops over the first few months of life outside the womb. Before the development of object permanence, it’s likely that the infant’s consciousness contains no notion of solidity and separateness. Everything is fluid; nothing is separate from anything else.

In terms of emotional development, the infant is believed to exist in a narcissistic bubble. All that exists is libido in love with libido.

Putting these together gives us a picture of an open, blissful, undifferentiated world.

This is exactly the experience that is recognizable from the writings of the mystics: undifferentiated awareness enjoying undifferentiated awareness. For example in the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali we read: “Tadā draṣṭuḥ svarūpe’vasthānam,” “Then the see-er abides in his own nature.”

In the mystical traditions, reaching this regressive state is given various glamorous names such as awakening, enlightenment, realization, etc. All these refer to essentially the same thing: reconnecting with early, pre-personal layers of consciousness.

How can regressive states be reached?

From the descriptions of human cognitive development and the possibility of undoing this development, the ways to reach it are almost obvious.

First you must abandon verbal, conceptual, or rational thought. You can see, if you study the literature, that a lot so-called spiritual teachers actively encourage the abandonment of verbal or discursive thinking.

This is a two-edged sword. It does take you closer to regression, but it also leaves you vulnerable to deception. If you abandon critical thinking, you have no way of telling whether you’re being deceived. We’ll come back to this danger in a moment; for now, let’s carry on with the path to regression.

Continuing with the journey toward the pre-personal, having reached a pre-verbal layer of the mind, you must continue in the same direction until there’s absolutely no movement left in the mind at all.

A well-documented description comes from Bernadette Roberts. Her practice was simply enjoying inner silence, sometimes for hours and hours at a time, every day when she could manage it, and keeping up this practice for decades. She writes about her enjoyment of silence at the start of her first book: [5]

Through past experience I had become familiar with many different types and levels of silence. There is a silence within, a silence that descends from without; a silence that stills existence and a silence that engulfs the entire universe. There is a silence of the self and its faculties of will, thought, memory, and emotions. There is a silence in which there is nothing, a silence in which there is something; and finally, there is the silence of no-self and the silence of God. If there was any path on which I could chart my contemplative experiences, it would be this ever-expanding and deepening path of silence.

If you’re familiar with Eastern traditions of meditation, you know they have many practices for cultivating still, silent, trance-like states of consciousness. These also eventually lead toward regression, called in the traditions by the names we have mentioned: awakening, realization, or enlightenment.

So if you want to reach enlightenment, sit still with your eyes closed for four hours at a time, every day, and keep this up for a year.

Hormesis is a phenomenon in biology in which something is beneficial in small quantities but harmful in large quantities. Examples would be stress or physical exercise. Small quantities energize you; large quantities exhaust you.

The notion of hormesis applies to regression. Regression gives you a motionless vantage point from which to observe adult consciousness. This vantage point brings clearer awareness of the way your conditioned mind works.

That awareness can be therapeutic. Marriage counselors would be out of business if both parties cultivated self-awareness! And stillness is beneficial in our frenetic, over-stimulated society.

The problem comes when you make stillness, awareness, and abiding in regressive states into goals in themselves and begin to believe this is the entire purpose of human life.

If stillness and awareness become the focus of your life, you become less and less functional at the ordinary business of living.

Back to Bernadette Roberts again, just as one example. She describes being unable to hold down a job as a schoolteacher: [6]

In a school where I taught it was a standing joke that whenever I lectured, anybody and everybody could crawl in and out the windows without my noticing a thing — as if I were blind or something! I regarded these antics as attention-getting behaviors and decided if I ignored them they would eventually wear themselves out — which proved to be true. But if I had the patience to win out, the administration did not. In the long run, I was fired for allowing this monkey business, and in leaving could not refrain from suggesting that instead of a teacher they hire a zookeeper.

She’d been trained as a schoolteacher but could no longer function as one. At home, caring for her own children, she absent-mindedly left her slippers in the refrigerator. [7] Her fixation on the inner world left her less and less able to function in the outer world.

If you search around, you can read other biographies of spiritual teachers who became incapable of carrying out the duties for which they had been trained. Sometimes they excuse this lack of functionality by framing it as spiritual progress.

Describing the regressive state as awareness in love with awareness sounds beautiful, but the state is a dead-end. Retreating into yourself isn’t growth.

The error compounds itself if you take your obsession with regression and turn it into an explicit value-system. This devalues the concrete and the ordinary. You are imposing a toxic value system on your experience.

Retreating from the world into one’s interior is sometimes thought of as typical of Eastern mysticism, but it exists also in Christianity. I’m thinking here of the seventeenth-century movement that came to be known as Quietism. (This was not their name for themselves; it was imposed by outsiders.)

The leader of the Quietists was a Spanish priest named Miguel de Molinos. Among the statements attributed to de Molinos were propositions such as, “It is necessary that man reduce his own powers to nothingness,” “To wish to operate actively is to offend God,” and “Vows about doing something are impediments to perfection.” [8] You can see that these statements eulogize an infantile and incapable way of life. In Molinos’ system of values, you’re supposed to do nothing. This is completely regressive. You’ve abdicated your adult powers and responsibilities.

To take an example from Eastern mysticism, an American social worker joined an Eastern regression cult and later explained: “Before I left for Pune, I was a very capable, articulate, professional woman. When I got back I was in a totally hypnotic state. I was absolutely helpless.” [9]

Given this impaired functionality, it’s no wonder so many enlightened individuals end up becoming cult leaders. It’s the only career path open to them.

I’ve said that becoming fixated on regressive states makes you less functional in ordinary life. But abiding in regressive states also makes you a danger to other people.

If you make regression your permanent home, you operate without a super-ego and without the normal societal conditioning. If you then encourage other people to abandon critical thinking, you are encouraging them to render themselves defenseless. This combination of a leader without scruples and vulnerable followers inevitably leads to exploitation and abuse.

The social worker just mentioned exemplifies the dark side of regression: the tendency for exploitative cults to form. The leaders of these regression cults are sometimes called “malignant narcissists.” They are totally in love with themselves, and they have none of the normal social restraints on their acting out.

They could equally be described as “traumatized infants with hypnotic powers.” An individual with access to regressive states automatically draws other people to themselves. People are attracted to their apparent freedom from reality by a hypnotic pull. This is already a form of trance induction. But a surprising number of cult leaders have made an intentional study of hypnosis. Their techniques are little known to the general public. They don’t involve the stereotypical verbal suggestions and dangling pocket-watches. Trance induction can be effected silently with stillness and eye gazing.

An Italian hypnotist named Marco Paret teaches the eye-gazing technique today. [10] This technique starts with learning to stare without blinking for longer and longer periods of time — up to 10, 20, or even 30 minutes. This practice actually has a name in India. It’s called trāṭaka. From the very fact it has a name, we can conclude it’s been known in India for much longer than in the West.

Fascination by the gaze gives the practitioner psychological power over people. This hypnotic gaze forms the basis for cult mind-control.

Most people are completely unaware that there even is such a thing as hypnotic fascination. Their lack of awareness is part of what makes regression cults so dangerous.

Also on YouTube, you can view the testimony of “Sally Jane,” a former professional hypnotist who is now a Christian. [11]

The fact that people addicted to regressive states can’t earn a living in the normal world makes it all the more tempting for them to gather “students” around themselves. These relationships are generally unproductive and benefit the “teacher” more than the “students.”

Regression cults are based on deception. At the very least, there is the deceptive teaching that regression is an advanced spiritual state and perhaps even the main goal of life.

[1] Sigmund Freud, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis, trans. G. Stanley Hall (New York: Horace Liveright, 1920), p. 295.

[2] Sigmund Freud, letter to Oskar Pfister, October 9, 1918.

[3] Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, trans. Joan Riviere (London: Hogarth Press, 1930), p. 11.

[4] Ibid., p. 22.

[5] Bernadette Roberts, The Experience of No-Self: A Contemplative Journey, revised edition (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press: 1993), p. 19.

[6] Bernadette Roberts, The Path to No-Self (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press: 1991), p. 140.

[7] Bernadette Roberts, The Experience of No-Self.

[8] Coelestis Pastor, 1687, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/innoc11/i11coel.htm.

[9] Win McCormack, “Bhagwan’s Mind Control,” New Republic, April 12, 2018, https://newrepublic.com/article/147902/bhagwans-mind-control.

[10] https://www.youtube.com/user/neurolinguistic. Marco Paret credits a certain Erminio di Pisa as his teacher, though this practitioner is unknown outside Paret’s references to him. Marco Paret also narrates that his friend Max Tira knew of a barber, Virgilio Torrizzano, who had mastered the art of the hypnotic gaze induction. He goes on to say that Torrizzano had learned fascination from a master, who may have been in the lineage of Alfred Édouard d’Hont, stage name Donato. Marco Paret believes that the lineage ultimately descends from Franz Anton Mesmer himself. The oldest published source they refer to is La fascination magnétique by Édouard Cavailhon (Paris: E. Dentu, 1882). This places Donato as the central figure of the narrative and includes a lengthy preface by him. Paret’s summary in Italian is at https://universite-europeenne.com/en/cose-la-fascinazione-istantanea-metodo-donato/.

[11] Heal and Restore, “Ex Hypnotist to Jesus Christ. The dangers of hypnosis,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxm3Ot3Agm0.